She was a day care worker and mother of three who died when a drug suspect being chased by Louisville police ran a stop sign and plowed into her vehicle on Oct. 23, 2012.

Stephanie Melson's death was the catalyst for newly arrived Louisville Metro Police Chief Steve Conrad to overhaul the department's pursuit policy to try and reduce the risk of collisions and fatalities from police chases.

The result, starting in December of 2012 and including several updates, is one of the strictest police pursuit policies in the country:

Officers can now only chase suspects if the person has been involved in a violent felony. If not, officers not only have to halt the chase, but, as of last year, they have to stop, turn around and drive the opposite direction to show the suspect they are not being followed. And, if an officer does give chase, he or she has to justify the pursuit to a commanding officer as soon as the pursuit starts.

The rule has led to a drastic reduction in pursuits, as well as accidents and injuries resulting from chases in the last three years compared to the prior three years, according to statistics provided by LMPD.

Seven people died in pursuits in the five years before the new policy began. But since 2013, there have been no deaths as a result of police chases, data shows.

"The whole idea behind the change was to reduce the opportunity for citizens and officers and people we are pursuing to get hurt," Conrad said in an interview with WDRB.

But the changes appear to have met some resistance, irritating some officers who believe the policy handcuffs police and encourages drivers to flee. Police used to be able to pursue anyone they believe committed any type of non-violent felony, such as theft or drug possession.

"I've heard defense attorneys who have told their clients (to run)," said one officer, who asked to remain anonymous. "There are stolen cars out there and these officers want to stop it and get the stolen car but we can't."

Louisville Fraternal Order of Police President Dave Mutchler did not return a phone call seeking comment about how he and other officers feel about the pursuit policy.

In the year after the policy was put in place, the number of pursuits plummeted, from 52 in 2012 to 12 in 2013 - a 77 percent decrease.

In the last two years, however, those numbers are trending back upwards. There were 23 pursuits in 2014 and 33 last year.

At the same time, more than a dozen officers have been disciplined for improper pursuits in the last two years, some of which have caused accidents and injuries. About one-fourth of the pursuits in 2014 and 2015 have resulted in disciplinary action. Several other pursuits are under investigation.

Conrad acknowledges that some defendants will get away because of the policy changes and that upsets officers.

"We're hired to catch the bad guys and letting someone go, even if they have committed a non-violent felony, rubs all of us the wrong way," Conrad said. "But that doesn't justify taking unnecessary risks."

Conrad pointed out that the percentage of pursuits resulting in wrecks is roughly 50 percent each year - underscoring the need to limit chases except when unavoidable.

"Even after you've weighed the risk, it is still an incredibly dangerous activity for everyone involved," Conrad said.

Another LMPD officer who spoke to WDRB agreed with the chief.

"I can understand the restrictions due to the liability for a chase that causes a death or injury," said the officer, who asked not to be identified because he had not been given permission to speak with the media.

Despite the uptick in pursuits in the last two years, the numbers are still way down compared with the years before Conrad implemented the policy.

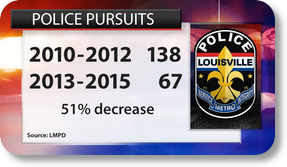

Pursuits have fallen by 51 percent in the three years since the new policy, compared with 2010-2012.

In the same time period, the percentage of injuries fell by 57 percent. Collisions were down 17 percent. And no one has been killed. From 2007 through 2012, 76 people were injured and seven died in pursuits, including 4- and 5-year-old girls who were crossing the street in 2008 when struck by a fleeing vehicle.

"I believe ... the numbers are heading in the right direction," Conrad said. "My goal is for the men and women who work for me to make it home and citizens not to get hurt in an unnecessary pursuit."

POLICE STRUGGLE WITH POLICY

If some Louisville officers have struggled with the change in policy, it would not be that unusual, according to a 2014 national study.

For example, police in Miami "initially struggled" with changing to a "violent felony only" chase policy in the 1990s, according to the study called "Police Pursuit Driving."

"Many times when a supervisor would terminate a pursuit there were 'chicken' noises made on the radio or officers would click their microphones to show displeasure," according to the study.

The Miami department changed its pursuit training, using data and stories about crashes and injuries, and began disciplining officers who violated the policy. In the two decades since the policy has been put in place in Miami, pursuits are no longer "the norm, most officers have never been in a pursuit," according to the study.

In Louisville, as the number of police chases has crept back up, more officers are being disciplined for improper pursuits. In 2015, more than a dozen officers were suspended or reprimanded for "pursuing a vehicle not involved in a violent felony" over the last two years. Only one officer was punished for the same violation in 2013.

For example, Det. Chris Keown was suspended for three days in July for a January 26, 2015, pursuit in which he chased someone who had not been involved in a violent felony, which resulted in a collision causing injuries, according to police disciplinary records obtained by WDRB.

The number of accidents and officers and civilians injured during pursuits in 2015 was the highest it's been since 2012.

"I think it's a good policy; it's a responsible policy, but a policy is only as good as the extent and the vigorousness with which you enforce it," said civil rights attorney Greg Belzley.

Belzley is an attorney for Jordan New, who claims in a federal lawsuit he was seriously injured, and nearly killed, on Sept. 10, 2014, when Officer Aaron Browning, at the time an undercover VIPER officer, ran into New's bicycle downtown while pursuing him following an alleged drug deal. New was dragged after being struck, according to the suit.

"This is not the nature of an offense that justifies the tremendous risk of harm to not only the subject and police officer but innocent bystanders," Belzley said. "This is the reason that these restrictions and these policies and procedures exist and they have got to be followed." Browning was later cleared by police of any wrongdoing.

It is one of at least four pending lawsuits against LMPD and the city regarding people injured in pursuits.

More than 5,000 bystanders and passengers have been killed in police car chases since 1979, and tens of thousands more were injured as officers pursued drivers at high speeds and in hazardous conditions, often for minor infractions, according to a 2015 analysis by USA Today.

In Kentucky, 171 people have been killed in police pursuits since 1979, including three officers, 99 fleeing drivers and 69 citizens, according to the newspaper. Of those, 21 people died in Jefferson County.

Nationally, data shows that police pursuits are most likely to be initiated for traffic infractions or other minor offenses.

Like Jefferson County, police in Milwaukee and Minnesota, among other places, have changed their policies in recent years to allow pursuits only when a violent felony has occurred.

A police chief in Milwaukee said the fear that dangerous criminals would escape "did not materialize," according to the 2014 national study on police pursuits. The chief, Edward Flynn ,has said most of the people who flee police "are fleeing for what turns out to be minor and foolish reasons."

And the study said opposition to the policy in Milwaukee came not from police, but from community groups and citizens.

"It's one thing for me to have a strict policy and I'm proud of it and it's been effective," Flynn told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in 2013. "But it wouldn't have had an impact if it had not been followed. An overwhelming number of officers have complied. It's a tribute to their willingness to change longstanding practices."

But the head of the city's police union told USA Today last year that chasing suspects maintains law and order and vehicle thefts have gone up since the pursuit policy was tightened.

"When crooks think they can do whatever they choose, that will just fester and foster more crimes," Milwaukee Police Detective Michael Crivello told the newspaper.

At the time of the change in 2012, the FOP's Mutchler told The Courier-Journal that "it's in our blood to go out and get the bad guys. It's very, very hard to be told you can't do that or there's a severe limitation on that. ... At the same time, there's no officer that wouldn't have an issue if a member of their family was killed because we wanted to catch a stolen Honda."

Conrad said the department doesn't have an analysis for the causes of why the number of pursuits has risen the last two years.

But he noted that "in the vast majority of cases, officers are making good decisions, they are driving with due regard for the safety of all. ... It means our officers are safer, our citizens are safer. Even the suspects we've had to chase are safer."